Gene Roddenberry

| Gene Roddenberry | |

|---|---|

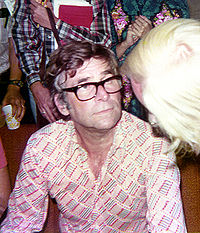

Roddenberry in 1976 |

|

| Born | Eugene Wesley Roddenberry August 19, 1921 , U.S. |

| Died | October 24, 1991 (aged 70) , U.S. |

| Other names | Robert Wesley |

| Occupation | Television producer and television writer |

| Spouse | Eileen-Anita Rexroat (1942–1969) Majel Barrett (1969–1991) |

| Gene Roddenberry | |

|---|---|

| Los Angeles Police Department | |

| August 19, 1921 – October 24, 1991 (aged 70) | |

| Place of birth | El Paso, Texas |

| Service branch | United States |

| Year of service | 1949 - 1956 |

| Rank | Sworn in as an Officer - 1949 |

| Relations | Majel Barrett |

| Other work | Creator of Star Trek, screenwriter, dramatist, television producer |

Eugene Wesley "Gene" Roddenberry (August 19, 1921 – October 24, 1991) was an American screenwriter, producer and futurist, best known for creating the American science fiction series Star Trek. Born in El Paso, Texas, he grew up in Los Angeles, California where his father worked as a police officer. Roddenberry flew combat missions in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II, and worked as a commercial pilot after the war. He later followed in his father's footsteps, joining the Los Angeles Police Department to provide for his family, but began focusing on writing scripts for television.

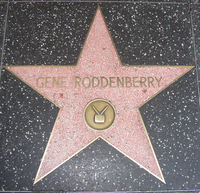

As a freelance writer, Roddenberry wrote scripts for Highway Patrol, Have Gun, Will Travel and other series, before creating and producing his own television program, The Lieutenant. In 1964, Roddenberry created Star Trek, and it premiered in 1966, running for three seasons before cancellation. Syndication of Star Trek led to increasing popularity, and Roddenberry continued to create, produce, and consult on Star Trek films and the television series, Star Trek: The Next Generation until his death. Roddenberry received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and he was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame and the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences' Hall of Fame. Years after his death, Roddenberry was one of the first people to have his ashes "buried" in space.

The fictional Star Trek universe Roddenberry created has spanned over four decades, producing five television series, 700 episodes and eleven films, with a twelfth film currently in development and scheduled for a 2012 release.

Contents |

Early life (1921–1940)

Gene Roddenberry was born on August 19, 1921, in El Paso, Texas,[1] (exactly half a century, to the day, after Orville Wright was born). His parents were police officer Eugene Edward Roddenberry and Caroline "Glen" Golemon Roddenberry.[2] He grew up in Los Angeles and attended Berendo Junior High School (now Berendo Middle School) before graduating from Franklin High School.

After graduation, Roddenberry took classes in Police Studies at Los Angeles City College and became head of the Police Club, liaising with the FBI. He went on to study at Columbia University, the University of Miami, and the University of Southern California but did not graduate.[2]

Military service and civil aviation (1941–1948)

Roddenberry developed an interest in aeronautical engineering and subsequently obtained a pilot's license. In 1941, he joined the United States Army Air Corps, which in the same year became the United States Army Air Forces. He flew combat missions in the Pacific Theatre with the "Bomber Barons" of the 394th Bomb Squadron, 5th Bombardment Wing of the Thirteenth Air Force and on August 2, 1943, Roddenberry was piloting a B-17E Flying Fortress named the "Yankee Doodle", from Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides when mechanical failure caused it to crash on take-off. In total, he flew eighty-nine missions for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal before leaving the Air Force in 1945.[3][4][5] After the military, Roddenberry worked as a commercial pilot for Pan American World Airways (Pan Am). He received a Civil Aeronautics commendation for his rescue efforts following a June 1947 crash in the Syrian desert while on a flight to Istanbul from Karachi.

Los Angeles Police Department (1949–1956)

Pursuing a career in Hollywood, Roddenberry left Pan Am and moved to Los Angeles. To provide for his family, he joined the Los Angeles Police Department on February 1, 1949. He became a Police Officer III in 1951 and was made a Sergeant in 1953.[6] On June 7, 1956, he resigned from the police force to concentrate on his writing career.[7] In his brief letter of resignation, Roddenberry wrote:

I find myself unable to support my family at present on anticipated police salary levels in a manner we consider necessary. Having spent slightly more than seven years on this job, during all of which fair treatment and enjoyable working conditions were received, this decision is made with considerable and genuine regret.[7]

Television and film career (1955–1991)

While Roddenberry worked for the LAPD, he wrote television scripts under the pseudonym "Robert Wesley" for the series Highway Patrol and both the TV and radio versions of Have Gun, Will Travel. In 1957, he wrote an episode for the Boots and Saddles western series entitled "The Prussian Farmer". In 1960, he wrote four episodes of the British (ITC Entertainment) made Australian western Whiplash.

Eventually, Roddenberry's dissatisfaction with his work as a freelance writer led him to produce his own television program. His first attempt, APO 923, was not picked up by the networks, but in 1963, he created and produced The Lieutenant, which lasted for a single season and was set inside the United States Marine Corps with Nichelle Nichols starring in the first episode.

Star Trek

Roddenberry developed Star Trek in 1964, developing it as a combination of the science-fiction series Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. Roddenberry sold the project as a "Wagon Train to the Stars", and it was picked up by Desilu Studios. The first pilot went over its US$500,000 budget and received only minor support from NBC. Nevertheless, the network commissioned an unprecedented second pilot and the series premiered on September 8, 1966 and ran for three seasons. The show began to receive low ratings, and in the final season, Roddenberry offered to demote himself to line producer in a final attempt to rescue the show by giving it a desirable time slot.

The series went on to gain popularity through syndication.[8]

Beginning in 1975, the go-ahead was given by Paramount for Roddenberry to develop a new Star Trek television series, with many of the original cast to be included. It was originally called Phase II. This series was the anchor show of a new network (the ancestor of UPN, which later became part of The CW Television Network), but plans by Paramount for this network were scrapped and the project was reworked into a feature film. The result, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, received a lukewarm critical response, but it performed well at the box office – it was the highest-grossing of all Star Trek movies until the release of First Contact in 1996.[9]

When it came time to produce the obligatory theatrical sequel, Roddenberry's story submission of a time-traveling Enterprise crew involved in the John F. Kennedy assassination was rejected. He was removed from direct involvement and replaced by Harve Bennett.[10] He continued, however, as executive consultant for the next four films: Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan; Star Trek III: The Search for Spock; Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home; and Star Trek V: The Final Frontier.

Roddenberry was deeply involved with creating and producing Star Trek: The Next Generation, although he only had full control over the show's first season. The WGA strike of 1988 prevented him from taking an active role in production of the second season and forced him to hand control of the series to producer Maurice Hurley.

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country was the last film with the cast of the original Star Trek series and was dedicated to Roddenberry. He reportedly viewed an early version of the film a few days before his death.[10]

In addition to his film and TV work, Roddenberry also wrote the novelization of Star Trek: The Motion Picture. It was published in 1979 and was the first of hundreds of Star Trek-based novels to be published by the Pocket Books unit of Simon & Schuster, whose parent company also owned Paramount Pictures Corporation. Because Alan Dean Foster wrote the original treatment of the Star Trek: The Motion Picture film, there was a rumor that Foster was the ghostwriter of the novel. This has been debunked by Foster on his personal web site. (Foster did, however, ghostwrite the novelization of George Lucas's Star Wars.) Roddenberry talked of writing a second Trek novel based on his rejected 1975 script of the JFK assassination plot, but he died before he was able to do so.[11]

Roddenberry is reported to have made comments regarding what was to be considered canonical material in the fictional Star Trek universe, even toward the end of his life. In particular, claims have been made about his expressed opinions in this regard for the films Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, and Star Trek: The Animated Series. See main article, Star Trek canon.

"Star Trek" is a rare instance of a television series gaining substantially in popularity and cultural currency long after cancellation (see main article, Cultural influence of Star Trek). Perhaps inevitably, then, there has been some contention over the years regarding proper attribution of artistic credit and assignment of royalties related to the show. A few writers and other production staff for the series have said that ideas they developed were later claimed by Roddenberry as his own, or that Roddenberry discounted their contributions and involvement. Roddenberry was confronted by some of these people, and he apologized to them; but according to at least one critic, he continued to claim undue credit.[12]

"Star Trek" theme music composer Alexander Courage long harbored resentment of Roddenberry's attachment of lyrics to his composition. By union rules, this resulted in the two men splitting the music royalties payable whenever an episode of Star Trek aired, which otherwise would have gone to Courage in full.[13] (The lyrics were never used on the show, but were performed by Nichelle Nichols on her 1991 album, "Out of this World.") Later, while cooperating with Stephen Whitfield for the latter's book The Making of Star Trek, Roddenberry demanded and received Whitfield's acquiescence for 50 percent of that book's royalties. As Roddenberry explained to Whitfield in 1968:

I had to get some money somewhere. I'm sure not going to get it from the profits of Star Trek.[14]

Herbert Solow and Robert H. Justman observe that Whitfield never regretted his fifty-fifty deal with Roddenberry since it gave him "the opportunity to become the first chronicler of television's successful unsuccessful series".[15]

Star Trek was used as the basis for further television series: Star Trek: The Next Generation; Star Trek: Deep Space Nine; Star Trek: Voyager; and Star Trek: Enterprise.

Other television work

Aside from Star Trek, Gene produced Pretty Maids All in a Row, a sexploitation film adapted from the novel written by Francis Pollini and directed by Roger Vadim. The cast included Rock Hudson, Angie Dickinson, Telly Savalas, and Roddy McDowall alongside Star Trek regulars James Doohan and William Campbell. It also featured Gretchen Burrell, the wife of country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons. Despite Roddenberry's expectations, the film was not a success.

In the early 1970s, Roddenberry pitched pilots for three sci-fi TV series concepts, although none were developed as series: The Questor Tapes; Spectre, and Genesis II. ABC asked to see another TV movie using the characters from Genesis II, but with more action, and Roddenberry produced Planet Earth. He was not, however, involved in a third TV Movie, Strange New World, which used some of the characters and situations from Planet Earth, but with a different origin story.

Roddenberry feared that he would be unable to provide for his family, as he was unable to find work in the television and film industry and was facing possible bankruptcy.

Personal life

In 1942, Gene Roddenberry married Eileen Rexroat. They had two daughters, Darlene and Dawn, but during the 1960s, he had affairs with Nichelle Nichols (said by Nichols to be the reason he wanted her on the show)[16] and Majel Barrett. Twenty-seven years after his first marriage, Roddenberry divorced his first wife and married Barrett in Japan in a traditional Shinto ceremony on August 6, 1969 and they had one child together, Eugene Wesley, Jr.[17]

Although Roddenberry was raised as a Southern Baptist, he instead considered himself a humanist and agnostic. He saw religion as the cause of many wars and human suffering.[18] Brannon Braga has said that Roddenberry made it known to the writers of Star Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation that religion and mystical thinking were not to be included, and that in Roddenberry's vision of Earth's future, everyone was an atheist and better for it.[19] However, Roddenberry was clearly not punctilious in this regard, and some religious references exist in various episodes of both series under his watch. The original series episodes "Bread and Circuses", "Who Mourns for Adonais?", and "The Ultimate Computer", and the Star Trek: The Next Generation episodes "Data's Day" and "The Next Phase" are examples. On the other hand, "Metamorphosis", "The Empath", "Who Watches the Watchers", and several others reflect somewhat, his Humanist/Agnostic views.

Roddenberry and his wife Majel were honored by the Space Foundation in 2002 with the Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award,[20] in recognition of their contributions to awareness of and enthusiasm for space.

Burial in space and posthumous series

Roddenberry died on October 24, 1991, of heart failure. On April 21, 1997, a capsule carrying a portion of Roddenberry's ashes, and the ashes of Timothy Leary and nineteen other individuals, was launched into orbit aboard a Pegasus XL rocket from near the Canary Islands. By 2004, the capsule's orbital height deteriorated and it disintegrated in the atmosphere. Another flight to launch more of his ashes into deep space along with those of Barrett, his widow who died in 2008, is planned for launch in 2012.[21]

After his death, Roddenberry's estate permitted the filming of Earth: Final Conflict and Andromeda, two television series which were based on his unused stories. A third story idea was adapted in 1995 as the comic book Gene Roddenberry's Lost Universe (later titled Gene Roddenberry's Xander in Lost Universe). Gene Roddenberry's Starship, was a computer-animated series that was proposed by Majel Barrett and John Semper but was not produced.[22]

References

- ↑ "Gene Roddenberry". Space Sciences (Macmillan Science Library). Gale. 2002. ISBN 002865546X.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 RODDENBERRY, GENE - The Museum of Broadcast Communications

- ↑ Freeman, Roger A., with Osborne, David., "The B-17 Flying Fortress Story", Arms & Armour Press, Wellington House, London, UK, 1998, ISBN 1-85409-301-0, page 74

- ↑ Alexander, David, "Star Trek Creator", ROC Books, an imprint of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Books USA, New York, June 1994, ISBN 0-451-54518-9, pages 75-76

- ↑ Edward B. Kiker (Winter/Spring 2004). "SOLDIERS OF VISION: We Don’t Stop When We Take off the Uniform" (PDF). Army Space Journal. http://www.smdc-armyforces.army.mil/Pic_Archive/ASJ_PDFs/ASJ_VOL_3_NO_1_Y_FLIP_1.pdf. Retrieved December 21, 2008. "He took part in 89 missions and sorties, and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal."

- ↑ David Alexander.(1994) "Star Trek Creator : The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry," Roc, p.104

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Alexander, p.141

- ↑ Sackett, Susan (2002). Inside Trek: My Secret Life with Star Trek Creator Gene Roddenberry. Hawk Publishing Group. ISBN 1-930709-42-0.

- ↑ Star Trek Movies: Which is the Best? by Neha Tiwan

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Susan Sackett (2002). Inside Trek: My Secret Life With Star Trek Creator Gene Roddenberry. HAWK Publishing Group. ISBN 1-930709-42-0.

- ↑ Starlog #16, September, 1978, "Star Trek Report" by Susan Sackett as quoted by "The God Thing: Gene Roddenberry's Lost Star Trek Novel" at http://www.well.com/~sjroby/godthing.html

- ↑ Engel, Joel (1994). Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek. Hyperion Books. ISBN 0786860049. Inside Star Trek: The Real Story (1996) commentary by Star Trek producer Herbert F. Solow, science-fiction convention talks by Star Trek writer Dorothy C. Fontana, and books and articles by Harlan Ellison.

- ↑ "Unthemely Behavior". Urban Legends Reference Pages. August 8, 2007. http://www.snopes.com/radiotv/tv/trek1.htm. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ Herbert F. Solow & Robert H. Justman, Inside Star Trek: the Real Story, Pocket Books, 1996, p.402

- ↑ Solow & Justman, p.402

- ↑ Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, G.P. Putnam & Sons, New York, 1994.

- ↑ David Alexander (1994). Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry. Roc. ISBN 0-451-45440-5.

- ↑ "Roddenberry Interview". The Humanist 51 (2). March/April 1991.

- ↑ Braga, Brannon (June 24, 2006). "Every religion has a mythology". International Atheist Conference. Reykjavik, Iceland. http://sidmennt.is/2006/08/16/every-religion-has-a-mythology/. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ↑ Foundation Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award

- ↑ "Ashes of 'Star Trek' Creator's Widow to Fly in Space". space.com. http://www.space.com/news/090127-majel-roddenberry-ashes-space.html.

- ↑ "Mainframe Entertainment Lands Gene Roddenberry's 'Starship' for Computer Animated Television Series". BNet Research Center. October 20, 1998. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0EIN/is_1998_Oct_20/ai_53099756. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

Further reading

- Alexander, David (1995). Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry. New York: Roc. ISBN 0451454405.

- Engel, Joel (1994). Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0786860049.

- Fern, Yvonne (1994). Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520088425.

- Gross, Edward; Mark A. Altman, Gene Roddenberry (1994). Great Birds of the Galaxy: Gene Roddenberry and the Creators of Star Trek. Boxtree. ISBN 075220968X.

- Sackett, Susan (2002). Inside Trek: My Secret Life with Star Trek Creator Gene Roddenberry. Hawk Publishing Group. ISBN 1930709420.

- Van Hise, James (1992). The Man Who Created Star Trek: Gene Roddenberry. Pioneer Books. ISBN 1556983182.

- Whitfield, Stephen E.; Gene Roddenberry (1968). The Making of Star Trek. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0345340191.

Cast autobiographies

- Doohan, James and transcribed by Peter David. Beam Me Up, Scotty: Star Trek's "Scotty" in his own words. ISBN 0-671-52056-3.

- Koenig, Walter. Warped Factors: A Neurotic's Guide to the Universe. ISBN 0-87833-991-4.

- Nichols, Nichelle. Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories. ISBN 1-57297-011-1. Published 1995.

- Nimoy, Leonard. I Am Not Spock. ISBN 978-0-89087-117-1. Published 1977.

- Nimoy, Leonard. I Am Spock. ISBN 978-0-7868-6182-8. Published 1995.

- Shatner, William and transcribed by Chris Kreski. Star Trek Memories. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-017734-9; ISBN 978-0-06-017734-8. Published 1993.

- Shatner, William and transcribed by Chris Kreski. Star Trek Movie Memories. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-017617-2. Published 1994.

- Solow, Herbert F. and Robert H. Justman. Inside Star Trek: The Real Story. ISBN 0-671-89628-8. Published 1999.

- Takei, George. To The Stars: The Autobiography of George Takei: Star Trek's Mr Sulu. ISBN 0-671-89008-5. Published 1994.

- Whitney, Grace Lee and transcribed by Jim Denney. The Longest Trek: My Tour of the Galaxy. Foreword by Leonard Nimoy. ISBN 1-884956-05-X; ISBN 978-1-884956-05-8. Published 1998.

External links

- Official Roddenberry family website

- Gene Roddenberry at the Internet Movie Database Retrieved on January 24, 2008

- Gene Roddenberry at Allmovie

- Gene Roddenberry at Memory Alpha (a Star Trek wiki)

- Gene Roddenberry at Find a Grave

- Gene Roddenberry at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database Retrieved on January 24, 2008

- The Museum of Broadcast Communication

- Strange New Worlds: The Humanist Philosophy of Star Trek by Robert Bowman, Christian Research Journal, Fall 1991, pp. 20 ff.

- StarTrek.com biography

- Gene Roddenberry: What Might Have Been... on Roddenberry's 70s failed pilots

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||